Ärzte Krone

Fortbildung, Informationen und Service für niedergelassene Ärzt:innen

Apotheker Krone

Fortbildung, Service und beratungsrelevante Informationen für die Tara

ARZT & PRAXIS

Das Magazin zur Diplomfortbildung in Österreich

AHOP-News

Special-Interest-Medium für hämatologisch und onkologisch tätige Pflegepersonen

DIABETES FORUM

Hot Topics der Diabetologie interdisziplinär und praxisbezogen aufgearbeitet

FAKTEN der Rheumatologie

„Die“ rheumatologische Fachzeitschrift Österreichs zu State of the Art, Wissenschaft und Forschung + jede Ausgabe mit DFP-Beitrag

GYN-AKTIV

Fachmagazin zur Frauenheilkunde für Kliniker:innen und Niedergelassene

NEPHRO Script

Offizielles Organ der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Nephrologie (ÖGN)

neurologisch

Offizielle Fachzeitschrift der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Neurologie (ÖGN)

PHARMAustria

Das Branchenmagazin für Führungskräfte und Entscheidungsträger der pharmazeutischen Industrie

Das Medizinprodukt

SPECTRUM Dermatologie

Facettenreiche Dermatologie: chronisch entzündlich, infektiös, onkologisch & mehr

SPECTRUM Onkologie

Aus der Forschung in die Praxis: Die Welt der Onkologie mit ihren vielen Gesichtern

SPECTRUM Pathologie

Pathologie als Weichensteller: Der präzise Blick für die exakte Diagnose

SPECTRUM Urologie

Am Ball bleiben auf einem breiten Themenfeld der Uro(onko)logie

SPECTRUM Psychiatrie

Fokusbezogene, aktuelle Themen aus Psychiatrie & psychotherapeutischer Medizin

Universum Innere Medizin

Streifzug durch die Innere Medizin im offiziellen Medium der ÖGIM

Fortbildung, Information und Service für Zahnmediziner:innen

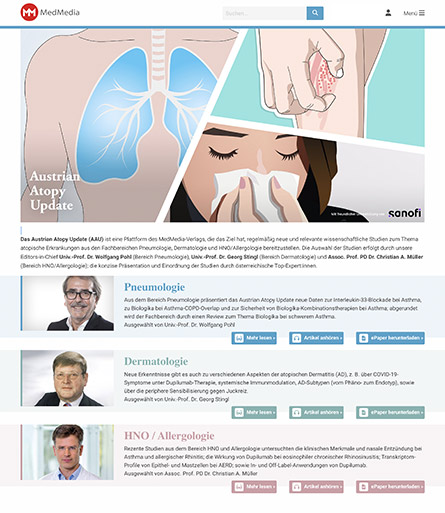

Austrian Atopy Update

Eine Plattform mit dem Ziel, regelmäßig neue und relevante wissenschaftliche Studien zum Thema atopische Erkrankungen bereitzustellen

car-t-cell

CAR-T-Zellen als Game Changer - kuratives Potential auf hohem Niveau

Case Report Interactive

Wissenschaftliche Evidenz und Empfehlungen aus der klinischen Praxis werden anhand eines konkreten Fallbeispiels vermittelt.

congress x-press

Expert:innen berichten Studienhighlights von (inter)nationalen Kongressen via Newsletter

DigitalDoctor

Zielgerichtete Therapie chronisch entzündlicher Dermatosen

derma-target

Das neue Portal für die Medizin der Zukunft

Expertenforum

5 Fragen zu einem Thema werden von 5 Fachexpert:innen beantwortet. Zusammengefasst und kommentiert von einem/einer zusätzlichen Experten/Expertin.

Fast Facts Interactive

Die crossmediale Kombination: komprimierte Key Messages einer Studie plus Infografiken und Animationen

IM FOKUS

Themenchannels mit Qualitätscontent on Demand

krebs:hilfe!

Fachmedium für die bestmögliche onkologische Patientenversorgung

mol-onko

Die Website für zielgerichtete Therapien in Hämatologie und Onkologie

nextdoc

Die Plattform für Jungmediziner:innen

Podcast

Gezielte Information über Produkte, Services für Gesundheitspersonal oder die breite Öffentlichkeit

RELATUS MED

Das Newsportal für Medizin und Gesundheitspolitik

RELATUS PHARM

Das Newsportal für Pharmazie und Gesundheitspolitik

Study Shortcut

Studien durch Animationsvideos leicht verständlich gemacht

Therapie News

Single-sponsored, monothematische Focus-Website

Bücher

Fachbücher mit Fokus Gesundheit verfasst für ein breites Publikum

Gesundheit verstehen

Leicht verständliche und wissenschaftlich fundierte Broschüren

Neue Horizonte

Journal der Österreichischen MS-Gesellschaft

Pocketguides

Alle relevanten Informationen zu einer Indikation, zusammengefasst strukturiert und im handlichen Format

Apps

Hier finden sie APPs für medizinisches Fachpersonal supported by MedMedia

Leistungsbeschreibung und Preise zu unseren MedMedia-Produkten für Print und Digital

Das MedMedia Team: über 60 Mitarbeiter:innen mit medizinischer und pharmakologischer Fachkompetenz

Werde Teil von unserem Team. Erfahre mehr über die Fima und Jobs bei MedMedia

MedMedia Verlag und Mediaservice GmbH

AdresseSeidengasse 9/Top 1.1, 1070 Wien

Telefon:+43 1 4073111-0

Fax:+43 1 4073114

Abonnieren sie hier Fachmagazine passend zu ihren Interessen oder Fachgebieten

Melden sie sich hier für die Newsletter passend zu ihren Interessen oder Fachgebieten an

Neu Registrieren

Ich habe noch kein Benutzerkonto und möchte mich kostenlos registrieren.

Zur RegistrierungHereditary Vestibulocerebellar Syndromes

Melden Sie sich bitte hier kostenlos und unverbindlich an, um den Inhalt vollständig einzusehen und weitere Services von www.medmedia.at zu nutzen.

Department of Neurology David Geffen School of Medicine at The University of California, Los Angeles

1 Parker HL. Periodic ataxia. Collect Papers Mayo Clinic Mayo Found 1946; 38:642–5

2 Jen JC et al., Primary episodic ataxias: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Brain 2007; 130:2484–93

3 VanDyke et al., Hereditary myokymia and periodic ataxia. J Neurol Sci 1975; 25:109–18

4 Browne DL et al., Episodic ataxia/myokymia syndrome is associated with point mutations in the human potassium channel gene, KCNA1. Nat Genet 1994; 8:136–40

5 Wang H et al., Localization of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2, two K channel proteins, to synaptic terminals, somata, and dendrites in the mouse brain. J Neurosci 1994; 14:4588–99

6 Papazian DM et al., Cloning of genomic and complementary DNA from Shaker, a putative potassium channel gene from Drosophila. Science 1987; 237:749–53

7 Jiang Y et al., The principle of gating charge movement in a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature 2003; 423:42–8

8 Jiang Y et al., X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature 2003; 423:33–41

9 Smart SL et al., Deletion of the K(V)1.1 potassium channel causes epilepsy in mice. Neuron 1998; 20:809–19

10 Herson PS et al., A mouse model of episodic ataxia type-1. Nat Neurosci 2003; 6:378–83

11 Ishida S et al., Kcna1-mutant rats dominantly display myokymia, neuromyotonia and spontaneous epileptic seizures. Brain Res 2012; 1435:154–66

12 Eunson LH et al., Clinical, genetic, and expression studies of mutations in the potassium channel gene KCNA1 reveal new phenotypic variability. Ann Neurol 2000; 48:647–56

13 Zuberi SM et al., A novel mutation in the human voltage-gated potassium channel gene (Kv1.1) associates with episodic ataxia type 1 and sometimes with partial epilepsy. Brain 1999; 122 ( Pt 5):817–25

14 Lee H et al., A novel mutation in KCNA1 causes episodic ataxia without myokymia. Hum Mutat 2004; 24:536

15 Shook SJ et al., Novel mutation in KCNA1 causes episodic ataxia with paroxysmal dyspnea. Muscle Nerve 2008; 37:399–402

16 Tan SV et al., Episodic ataxia type 1 without episodic ataxia: the diagnostic utility of nerve excitability studies in individuals with KCNA1 mutations. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013; 55:959–62

17 Graves TD et al Episodic ataxia type 1: clinical characterization, quality of life and genotype-phenotype correlation. Brain 2014; 137:1009–18

18 Jen J et al.,Clinical spectrum of episodic ataxia type 2. Neurology 2004; 62:17–22

19 Imbrici P et al., Late-onset episodic ataxia type 2 due to an in-frame insertion in CACNA1A. Neurology 2005; 65:944–6

20 Cuenca-Leon E et al., Late-onset episodic ataxia type 2 associated with a novel loss-of-function mutation in the CACNA1A gene. J Neurol Sci 2009; 280:10–4

21 Wiest G et al., Otolith function in cerebellar ataxia due to mutations in the calcium channel gene CACNA1A. Brain 2001; 124:2407–16

22 Baloh RW et al., Familial episodic ataxia: clinical heterogeneity in four families linked to chromosome 19p. Ann Neurol 1997; 41:8–16

23 Denier C et al., High prevalence of CACNA1A truncations and broader clinical spectrum in episodic ataxia type 2. Neurology 1999; 52:1816–21

24 Griggs RC et al., Hereditary paroxysmal ataxia: response to acetazolamide. Neurology 1978; 28:1259–64

25 Strupp M et al., A randomized trial of 4-aminopyridine in EA2 and related familial episodic ataxias. Neurology 2011; 77:269–75

26 Strupp M et al., Treatment of episodic ataxia type 2 with the potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine. Neurology 2004; 62:1623–5

27 Ophoff RA et al., Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell 1996; 87:543–52

28 Mori Y et al., Primary structure and functional expression from complementary DNA of a brain calcium channel. Nature 1991; 350:398–402

29 Simms BA, Zamponi GW. Neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels: structure, function, and dysfunction. Neuron 2014; 82:24–45

30 Payandeh J et al., The crystal structure of a voltagegated sodium channel. Nature 2011; 475:353–8

31 Wan J,Carr et al., Nonconsensus intronic mutations cause episodic ataxia. Ann Neurol 2005; 57:131–5

32 Labrum RW et al., Large scale calcium channel gene rearrangements in episodic ataxia and hemiplegic migraine: implications for diagnostic testing. J Med Genet 2009; 46:786–91

33 Riant F et al., Identification of CACNA1A large deletions in four patients with episodic ataxia. Neurogenetics 2010; 11:101–6

34 Riant F et al., Large CACNA1A deletion in a family with episodic ataxia type 2. Arch Neurol 2008; 65:817–20

35 Wan J et al., Large Genomic Deletions in CACNA1A Cause Episodic Ataxia Type 2. Front Neurol 2011; 2:51

36 Ducros A et al., The clinical spectrum of familial hemiplegic migraine associated with mutations in a neuronal calcium channel. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:17–24

37 Zhuchenko O et al., Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA6) associated with small polyglutamine expansions in the alpha 1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel. Nat Genet 1997; 15:62–9

38 Jen J et al., A novel nonsense mutation in CACNA1A causes episodic ataxia and hemiplegia. Neurology 1999; 53:34–7

39 Geschwind DH et al., Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Frequency of the mutation and genotype-phenotype correlations. Neurology 1997; 49:1247–51

40 Jodice C et al., Episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2) and spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6) due to CAG repeat expansion in the CACNA1A gene on chromosome 19p. Hum Mol Genet 1997; 6:1973–8

41 Wan J et al., CACNA1A mutations causing episodic and progressive ataxia alter channel trafficking and kinetics. Neurology 2005; 64:2090–7

42 Wappl E et al., Functional consequences of P/Q-type Ca2+ channel Cav2.1 missense mutations associated with episodic ataxia type 2 and progressive ataxia. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:6960–6

43 Page KM et al., N terminus is key to the dominant negative suppression of Ca(V)2 calcium channels: implications for episodic ataxia type 2. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:835–44

44 Page KM et al., Dominant-negative calcium channel suppression by truncated constructs involves a kinase implicated in the unfolded protein response. J Neurosci 2004; 24:5400–9

45 Jeng CJ et al., Dominant-negative effects of episodic ataxia type 2 mutations involve disruption of membrane trafficking of human P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Cell Physiol 2008; 214:422–33

46 Jouvenceau A et al., Human epilepsy associated with dysfunction of the brain P/Q-type calcium channel. Lancet 2001; 358:801–7

47 Ishikawa K et al., Cytoplasmic and nuclear polyglutamine aggregates in SCA6 Purkinje cells. Neurology 2001; 56:1753–6

48 Ishikawa K et al., Clinical, neuropathological, and molecular study in two families with spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999; 67:86–9

49 Watase K et al., Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 knockin mice develop a progressive neuronal dysfunction with age-dependent accumulation of mutant CaV2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:11987–92

50 Hoebeek FE et al., Increased noise level of purkinje cell activities minimizes impact of their modulation during sensorimotor control. Neuron 2005; 45:953–65

51 Walter JT et al., Decreases in the precision of Purkinje cell pacemaking cause cerebellar dysfunction and ataxia. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9:389–97

52 Alvina K, Khodakhah K, KCa channels as therapeutic targets in episodic ataxia type-2. J Neurosci 2010; 30:7249–57

53 Mark MD et al., Delayed postnatal loss of P/Q-type calcium channels recapitulates the absence epilepsy, dyskinesia, and ataxia phenotypes of genomic Cacna1a mutations. J Neurosci 2011; 31:4311–26

54 Maejima T et al., Postnatal loss of P/Q-type channels confined to rhombic-lip-derived neurons alters synaptic transmission at the parallel fiber to purkinje cell synapse and replicates genomic Cacna1a mutation phenotype of ataxia and seizures in mice. J Neurosci 2013; 33:5162–74

55 Salvi J et al., RNAi silencing of P/Q-type calcium channels in Purkinje neurons of adult mouse leads to episodic ataxia type 2. Neurobiol Dis 2014; 68:47–56

56 Steckley JL et al., An autosomal dominant disorder with episodic ataxia, vertigo, and tinnitus. Neurology 2001; 57:1499–502

57 Cader MZ et al., A genome-wide screen and linkage mapping for a large pedigree with episodic ataxia. Neurology 2005; 65:156–8

58 Farmer TW, Mustian VM. Vestibulocerebellar ataxia. A newly defined hereditary syndrome with periodic manifestations. Arch Neurol 1963; 8:471–80

59 Damji KF et al., Periodic vestibulocerebellar ataxia, an autosomal dominant ataxia with defective smooth pursuit, is genetically distinct from other autosomal dominant ataxias. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:338–44

60 Escayg A et al., Coding and noncoding variation of the human calcium-channel beta4-subunit gene CACNB4 in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and episodic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66:1531–9

61 Burgess DL et al., Mutation of the Ca2+ channel beta subunit gene Cchb4 is associated with ataxia and seizures in the lethargic (lh) mouse. Cell 1997; 88:385–92

62 Jen JC et al., Mutation in the glutamate transporter EAAT1 causes episodic ataxia, hemiplegia, and seizures. Neurology 2005; 65:529–34

63 Kawakami H et al., Cloning and expression of a human glutamate transporter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994; 199:171–6

64 Yernool D et al., Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature 2004; 431:811–8

65 Winter N et al., A point mutation associated with episodic ataxia 6 increases glutamate transporter anion currents. Brain 2012; 135:3416–25

66 de Vries B et al., Episodic ataxia associated with EAAT1 mutation C186S affecting glutamate reuptake. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:97–101

67 Kerber KA et al., A new episodic ataxia syndrome with linkage to chromosome 19q13. Arch Neurol 2007; 64:749–52

68 Conroy J et al., A novel locus for episodic ataxia:UBR4 the likely candidate. Eur J Hum Genet 2014; 22:505–10

69 van de Leemput J et al., Deletion at ITPR1 underlies ataxia in mice and spinocerebellar ataxia 15 in humans. PLoS Genet 2007; 3:e108

70 Huang L et al., Missense mutations in ITPR1 cause autosomal dominant congenital nonprogressive spinocerebellar ataxia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012; 7:67

71 Dudding TE et al., Autosomal dominant congenital non-progressive ataxia overlaps with the SCA15 locus. Neurology 2004; 63:2288–92

72 Julien J et al., Sporadic late onset paroxysmal cerebellar ataxia in four unrelated patients: a new disease? J Neurol 2001; 248:209–14

73 Damak M et al., Late onset hereditary episodic ataxia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009; 80:566–8

74 Cha YH et al., Episodic vertical oscillopsia with progressive gait ataxia: clinical description of a new episodic syndrome and evidence of linkage to chromosome 13q. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;

78:1273–5

75 Steinlin M. Non-progressive congenital ataxias. Brain Dev 1998; 20:199–208

76 Illarioshkin SN et al., X-linked nonprogressive congenital cerebellar hypoplasia: clinical description and mapping to chromosome Xq. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:75–83

77 Zanni G et al., X-linked congenital ataxia: a new locus maps to Xq25-q27.1. Am J Med Genet A 2008; 146A:593–600

78 Zanni G et al., Mutation of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase isoform 3 in a family with X-linked congenital cerebellar ataxia impairs Ca2+ homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:14514–9

79 Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature 1993; 361:315–25

80 Hirota J et al., Carbonic anhydrase-related protein is a novel binding protein for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1. Biochem J 2003; 372:435–41

81 Jen JC et al., Genetic heterogeneity of autosomal dominant nonprogressive congenital ataxia. Neurology 2006; 67:1704–6

82 Klein A et al., Episodic ataxia type 1 with distal weakness: a novel manifestation of a potassium channelopathy. Neuropediatrics 2004; 35:147–9

83 Boel M, Casaer P, Familial periodic ataxia responsive to flunarizine. Neuropediatrics 1988; 19:218–20

84 Ilg W et al., Consensus paper: management of degenerative cerebellar disorders. Cerebellum 2014; 13:248–68

neuro 02|2014